Note: This was originally posted shortly after Jesse Lee Peterson's book was published, reposted in 2005, and now because of a fight between black customers and a Korean merchant in Dallas, Texas.

Scam? Yo Momma!

During the summer of 2002 I was an observer to a dispute between the Asian owners of a Chinese takeout and some of their black customers in Washington, D.C. The month-long boycott began when a local activist accused a cook at a Chinese takeout of attempting to cook a piece of chicken he had allegedly dropped on the floor.

Despite the best efforts of human rights activist Dick Gregory, popular talk-show host Joe Madison, and Rev. Walter Fauntroy, the protestors were unable to coax any media to report on the protest. On some days there were, by my unofficial count, as many as 100 people chanting songs and marching. But one key person was missing: Rev. Jesse Jackson.

It was important to the foot soldiers at the boycott that someone from the media report on the incident. It was clear that they wanted someone outside of the neighborhood to hear their complaint. The first few days I was asked by protestors if I was a reporter from Fox News or USA-9. I talked to everyone who approached me and did start acting like a reporter, taking notes until I got threatened a few days later by one of the angrier folks there. One woman, disappointed I was not with the media, began to complain about the media. Her main point: NBC and the Washington Post would be there if Jesse Jackson or Al Sharpton showed up.

A couple of days into the protest there was chatter that the leaders of the boycott had been in contact with Jesse Jackson, but that Jackson was headed to a different event (I believe it was the beating of a young black man in Los Angeles). One of the protestors told me: "See! Jesse ain't out for nobody but Jesse."

It was the type of scene that black conservatives have denounced on many occasions. Instead of focusing their energy on the local troubled schools or other pressing community issues, the boycotters were heaping their scorn on a small Chinese takeout. How likely is it that many of the people out protesting have since shown up to a PTA meeting or gotten involved with their local schools in other ways? After observing one of the protests, I did some research about the local schools. There are five of them in that particular ward. The one with the highest average SAT score? 736. That is almost 300 points below the national average.

It is also the type of scene that ends up a footnote in Rev. Jesse Lee Peterson's book Scam: How the Black Leadership Exploits Black America. Peterson is often referred to as "the other Jesse" or the "anti-Jesse Jackson." He has gained those nicknames as a result of his many media appearances denouncing Jackson and other civil rights leaders for allegedly turning their backs on the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. That legacy, Peterson says, has been abandoned by hustlers and problem profiteers who keep racial problems in the news so they make their careers off the backs of blacks.

To further dramatize the issue, Peterson holds an annual National Repudiation Day of Jesse Jackson. Peterson says that he will hold the event until Jesse Jackson "repents of his wrongs." I suspect that Peterson will be waiting a long time, assuming that he outlives Jackson. The day of Repudiation sounds like it would be great fun for anyone looking to denounce Jackson. But Peterson takes it all too seriously.

There is probably a lot of truth to what Peterson writes, especially about opportunistic black leaders. But in reading Peterson's long rant about civil rights leaders, I am reminded of Frederic Bastiat's statement that "the worst thing that can happen to a good cause is, not to be skillfully attacked, but to be ineptly defended."

Instead of putting forth a serious case of what is wrong with Jesse Jackson and other blacks often called leaders, Peterson goes for the easy shots. His style has made it easy for opponents to mock him. It did not have to be that way, considering Peterson's background. He was born into a "broken family in the tiny town of Comer Hill, Alabama." He was raised by his grandmother after his own mother abandoned him. He did not meet his father until he was 13 years old. He began to use drugs as a teen and got on welfare when he moved from Alabama to Los Angeles. As an adult he has worked in urban areas helping youth and others to turn around their lives.

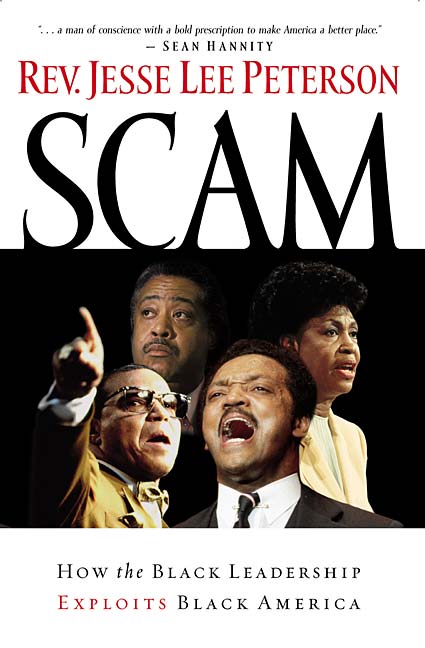

It is, however, his career as a civil rights leader critic that has gotten Peterson denounced as a sellout and Uncle Tom. The good reverend fights fire with fire, writing an unnecessarily negative book with cartoonish name-calling. He denounces the name calling, then engages in it for most of the book. Occasional name-calling is fine, but not a substitute for an argument. The cover of the book captures its essence.

Al Sharpton is looking slightly befuddled. Louis Farrakhan looks strange. Jesse Jackson has his mouth wide-open. And Maxine Waters, who isn't particularly significant, is pictured although it is tough to call her much of a leader. So she's in the background. But the main point is that it is a personal diatribe in which personalities are more important than ideas.

Peterson writes that black leaders are "corrupt," "problem profiteers," "skillful manipulators," "true enemies of black America," and "racial hucksters" who use their "racist minions" to shakedown corporations and cower whites into submission. Black pastors and preachers simply "parrot" Rev. Jackson and Rev. Al Sharpton, "spreading racial hatred through their sermons." At times Rev. Peterson seems to be playing a game trying to squeeze many negative adjectives into sentences about the people he does not like. On one page Rev. Louis Farrakhan is a "racist and anti-American hatemonger." On others, Farrakhan is "one of the most dangerous men in the nation" who is a "world-class racist." On top of that, he denounces Farrakhan as an "American Hitler."

Peterson's hyperbole leads him to dismiss Nelson Mandela as a "communist-socialist pig." Search my blog and you'll see that I have had critical things to say about Mandela and the other leaders Peterson rails against. But his off-handed dismissal of Mandela is a perfect example of what's wrong with the book. There are many things to disagree with Mandela about. But considering his 4 or 5 decade career fighting for various causes, it isn't intellecutally honest to just dismiss him as "communist-socialist pig" without even an explanation.

Mandela is dismissed with the same wave of the hand that dismisses rapper Jay-Z as "nothing more than a "street hoodlum" and rap music as encouraging a lifestyle that is "depraved." Dr. Leonard Jeffries, who hasn't been drawing controversy to himself since the early 1990s, is an Afrocentrist professor and professional racist." Maxine Waters, who is pictured on the cover but doesn't get her own chapter in the book, is a "professional agitator." Diane Watson, a member of the Oakland School Board that approved the use of Ebonics in 1997, is accused by Peterson of being in the same league as other black leaders trying to "control black people" for "their personal gain." Even movie director Spike Lee gets added to the mix, denounced as a "famous black racist" who, like Farrakhan, is a "black racist leader" who spreads falsehoods. Since when has movie director Spike Lee been recognized as a leader? Admittedly, I haven't paid for a Spike Lee movie ever since I heard him say that he doesn't care what people say about him, as long as they pay to see his movies. But I doubt that he has somehow become a leader because of his movies.

In a way, Peterson does what he accuses the media and whites of doing--turning anyone black and liberal who speaks into a microphone or on a street corner into a leader. What is it that Spike Lee has done that would make anyone think that he is a leader?

Peterson is probably at his best in the titles of the chapters. "Why Black Women Are So Mean" will make a lot of not-so-mean black women quite angry. "Instead of Reparations, How About a Ticket Back to Africa" might get some folks to purchase tickets to wherever Peterson is so they can punch him out. "Boycotting the NAACP" and "Al Sharpton, Riot King," are quite good. And then of course there is, "Louis Farrakhan, American Hitler." As bad as Farrakhan may be, can he really be called a Hitler?

Once you've denounced someone as Hitler or a devil, what's the worst thing you can call them when they do something else even worse?

Recall back a few months ago Rush Limbaugh when announced that he was addicted to pain-killers. He has been demonized by his critics over the years. When the drug addiction was revealed, his critics tried so hard to use it to kill his career. But they had shot their wad. There isn't much more new they can say about him. Limbaugh The Devil had become Limbaugh The Devil . . . With a Pill Addiction. I guess that the devil can somehow become worse because of that. The same with Bush-haters denouncing George W. Bush as Hitler. If he's already Hitler before the campaign has begun, what do you call him when he does something you don't like? And why would Hitler agree to help out immigrants who are currently illegal? Hitler wouldn't want to make a buck off them, he'd want them dead.

The same with Peterson's attack on Farrakhan, who, as far as I know, hasn't killed anyone Jewish. What do we call Farrakhan if he really does wipe out a few millions Jews, considering that the Hitler card has already been played when Jews were still healthy in his presence? The hyperbole from Peterson makes it hard to takes his arguments seriously even when he is correct. All authors probably want to be thought-provoking. But instead of nodding my head in agreement with Peterson when I do actually agree with him, I find myself checking my premises. How in the world can I agree with someone so bad at making his case?

Even if everything Rev. Peterson says about black leaders is true, what about the responsibility of blacks to ignore their siren song? Peterson says that blacks have been lied to, but only a fool can keeping getting fooled. Instead of looking seriously at that, black Americans are included among Rev. Peterson's sweeping generalizations.

I bet that black leaders WISH they had the kind of control that Peterson believes that they have. I recall a joke I heard years ago. Two Jewish men are reading their favorite newspapers. The first guy is reading a Jewish paper called The Forward. His friend is reading a Nazi paper. The guy reading The Forward begins to criticize his friend for reading anti-Semitic trash put out by the Nazis. But the guy says that he reads the Nazi paper to feel better about Jews. After all, he says, he can read that Jews control the media, Hollywood, the banking industry, the United Nations, etc.

The same is true with Peterson's book. Black leaders who complain about the lack of unity among blacks only need to read Peterson's book. In it they possess magical powers to have blacks do whatever it is they want. They can lead blacks around like sheep, telling them what to say, do, and think.

According to Peterson, Rev. Jackson and others are "brainwashing" blacks. Blacks are being "led around like sheep." He even asserts: "These current leaders tell blacks how to think, whom to vote for, and how to live their lives." Rev. Jackson and others have "put blacks into a trance-like state." Blacks "obey blindly" the wishes and desires of Rev. Jackson. In addition to paranoia, "blacks see racism everywhere."

His name-calling and sweeping generalizations call into question Rev. Peterson's other analysis, including those with blacks he has personally worked with. His work with troubled boys has taught him that "many black males are both lazy and irresponsible." On other another page, he writes that the "typical black male I work with has no work ethic, has little sense of direction in his life, is hostile towards whites and women, has an attitude of entitlement, and has an amoral outlook on his life." That analysis isn't that far of a jump from the rest of what he has written. And that analysis could be correct--after all, Rev. Peterson is discussing his work with troubled boys. But that's what his overblown rhetoric does--I find myself questioning even Peterson's observations about people he has worked with.

The sweeping generalizations do pretty much what Rev. Peterson charges Rev. Jackson and others with doing: taking away personal responsibility from blacks. Even if Rev. Peterson is correct about everything he says, certainly adult black Americans share some responsibility for allowing themselves to be led around by civil rights leaders.

Peterson writes that it is "time someone stood up to Jesse Jackson" and the others who are "fleecing the flock instead of leading them to spiritual and physical freedom" and that blacks must "throw off the oppression of their civil rights leaders and learn to stand on their own." But based on his analysis, there are two problems. One, if blacks are so easily led, why should anyone expect them to stand up to their leaders? Two, instead of standing up to Rev. Jackson, why not offer an alternative vision? Rev. Jackson has been attacked by enough people that it should be clear by now that he has a Teflon-shield. If blacks are ready to stand up to their crooked leaders, then Peterson should be ready to offer a clear vision. As philosophy Eric Hoffer wrote, "It is not actual suffering but a taste of better things which excites people to revolt." That's to say: Instead of beating up on others, or trying to convince blacks that their leaders are lousy, why not offer something better?

Rev. Peterson has the background that would have allowed him to offer an alternative vision. But his name-calling and attacks in the first half of his book make it unlikely that people will actually read through to the second half of the book, when Rev. Peterson does begin to lay out his mostly religious view of how black America needs to improve. After so many exaggerated attacks, including on the very people he wants to save, it is tough to take him seriously. He does eventually get around, in the final chapter, to saying what he believes needs to be done. The topics of the chapter: 1) Restore God's Order; 2) Commit to Prayer; 3) Forgive; 4) Commit to Marriage; 5) Judge by Character, Not Color; 6) Become Independent of Leaders; 7) Repudiate "Black Culture" 8) Embrace Work and Entrepreneurship 9) Commit to Education; 10) Commit to True Racial Reconciliation.

Rev. Peterson's frustration level at the amount of respect that Farrakhan and Jackson continue to receive from blacks is evident in the pages of his book, so much so that I'm surprised that Peterson hasn't dropped the "e" in his first name, so he would be called Jess instead of Jesse. Blacks supposedly are getting hoodwinked by their own leaders. I would suggest that there are some other reasons that the mass of civil rights leaders cited by Peterson are still respected by blacks.

The first one is very simple: civil rights leaders love them. I realize in some cases that the civil rights leaders may love themselves more than they love blacks. But the point is that blacks know that Farrakhan, Jackson, or lesser known leaders will be there when they are needed. At least, that was how I explained it when I was in South Korea in 1995 as the Million Man March was taking place. I seriously thought about flying from South Korea to participate in the March. (By the way, Peterson dismisses the March, saying that he "watched as hundreds of thousands of weak black men" attended it.)

Asked by an editor in South Korea to write about the March, I wrote a piece called "The Wrath of Farrakhan" trying to explain why Farrakhan remained so popular among blacks despite the controversies surrounding him. After all, after three decades of "Great Society" programs, civil rights laws, forced busing, affirmative action, and endless discussions about race, it had come to an all-black Million Man March being led by someone accused of being bigoted, anti-Semitic, homophobic, sexist, and racial separatist? I speculated that there were two main reasons, and the first one was very simple: he loves them.

When a group is looking to solve serious problems, I wrote, I suspect that the members will turn to people who love them first and foremost. This may explain why Malcolm X, Farrakhan's predecessor at the Nation of Islam, has in many ways eclipsed Martin Luther King. Whereas Dr. King urged blacks to love all people, Malcolm X told blacks that they needed to love themselves first. At a time most blacks feared defying whites, Malcolm X boldly responded to stereotypes of blacks by calling whites "blue-eyed devils." Instead of turning the other cheek, as Dr. King counseled, Malcolm X said that blacks needed to seize their rights "by any means necessary." One of Malcolm's favorite jokes was: "What do you call a Negro with a Ph.D.?" Answer: Nigger. In other words, you're always black in white eyes, and I'm always with you. Or, as I heard in South Korea: Who can spit in the eye of a man who is smiling at you?

On many occasions, I see brotherly love expressed among black men that might seem strange. The embrace that comes with the handshake. If you listen to black talk radio, you'll hear something very strange: black adults, especially men, telling each other, "I love you," as the caller or guest hangs up the phone. I can sense that they really feel that they are in a struggle and they are coming together, even when they are just yakking on the radio. I sense that black leaders have tapped into that. But they don't have to worry because their critics don't listen to them. They don't hear Jesse Jackson calling into black radio shows, the big time celebrity chatting away with callers who may not be able to pay their bills. And Jackson's critics don't hear him telling the callers and the hosts, "luv ya."

I suspect it is that love of black people that even explains why the Nation of Islam has shown willingness to embrace Michael Jackson.

A second reason many blacks continue to defend leaders like Rev. Jackson and Farrakhan is their message of self-help. In many cases, I know, it is just a message of self-help, without any real follow-up action. But in many cases, the self-help is a chance to poke whitey in the eye. The Million Man March was a resounding repudiation of big government. "We're not coming to beg Washington," Farrakhan said before the march. "Our day of begging white folk to do for us what we could do for ourselves is over." Whereas Dr. King asked blacks to find the good even in their oppressors, Farrakhan tells blacks to observe the devastating results of the "Great Society." The percentage of black families with two-parent households decreased from 78 percent in the 1960s to 40 percent by 1990. Black illegitimacy, which officially stood at 17 percent, is well above 70 percent. Black neighborhoods, relatively safe until the 1960s, are now rife with violence and crime.

That may even be a reason that Farrakhan had started to eclipse Jackson. Whereas Jackson is still holding his hand out, asking for more welfare and programs, Farrakhan has given that same system the finger. To be clear, I do believe that Rev. Jackson and some of the other leaders that Peterson mentions spend too much time trying to shake down government. If the government weren't there with promises of handouts, it is possible that someone like Al Sharpton would conclude that he could best help blacks by opening a rib joint in Harlem instead of running for president.

A third reason that I would say black leaders continue to enjoy respect from blacks, even when they don't agree with them, has to do with the protest I was attending: Jesse brings cameras. The other leaders of the protest, try as they might, couldn't get cameras. Joe Madison even talked about the boycott on his radio show several times. I don't say that as a fan of his. He, his callers and his guests have denounced me on several occasions, and after the boycott, we had an on-air knock-down, drag-'em out fight, and then after his producer hung up on me, he, his guest, and his callers talked about me for much of the next hour.

But think about it this way: You feel that you've been wronged; in most cases, you are not going to get cameras to highlight your problem; in many cases, you may not even know to whom you should turn. And in walks Jesse, with cameras in close pursuit. Your problem may become a national issue. Not only do you have media people asking you about the issue, but you may even end up a footnote in a book written by a conservative!

Instead of having magical powers to get blacks to do what they want, I suspect that the black leaders denounced in Peterson's book have the smarts to get in front of a protest. Instead of guiding the crowd, they figure out which crowd is most likely to hang with them. The same may be true of their relationship with the media. I agree with those who say that black leaders often have the wrong focus. Instead of dealing with tough issues, they'll rush to cases with cameras. The demand for dramatic confrontations may just result in such scenes being supplied. And one thing I wonder about people who say that black leaders have the wrong focus: do you really want Jesse Jackson or Maxine Waters focusing more of their energies on trying to fix education in the country? Perhaps education is better off with them rushing off to pointless protests.

There are some complexities in the relationship between black leaders and blacks that make it silly to just dismiss it all as "fleecing the flock." Peterson and others can say that blacks have been lied to, but there are others offering alternative visions as well as telling "the truth." Black adults can't be blameless. We can't just say that Jesse is telling lies and pointing to the white man like a crooked card dealer trying to distract us as she shuffles the cards. If blacks had been locked away in rooms without TVs, radio, newspapers, or books, then perhaps it could make sense to say black leaders are controlling them and telling them what to do and say, as Peterson says.

I even see the push for unity among many black Republicans I know. Just last night I attended a gathering of black Republicans in northern Virginia. I told them that I'm not a Republican, but they invited me anyway, I guess because they were looking for honest feedback. Or it may be that they are desperate enough that they must recruit me.

During the meeting, as we talked about which direction the organization they are talking about should take if formed, one member kept saying, "We've got to build ourselves." He kept repeating the phrase. Finally, as he was talking, I took out a sheet of paper and wrote, "Build Ourselves" in large letters, and then held it up everytime he started to say it. I got a laugh out of it, including from him, but the point was clear: blacks have got to do some things on their own.

That message isn't that far removed from what Farrakhan, Jackson, Waters, and Sharpton say, at least in theory. Of course their actions may be different, with Jackson, Waters and Sharpton then demanding that Congress set up a commission, whereas the black Republicans head out to raise money. Jackson, Farrakhan and others no doubt engage in the same overblown rhetoric that Peterson does, with the result that all of their good works are easily ignored. And that is exactly what is happening with Peterson, who is making more of a career off his civil rights bashing than with his work helping troubled boys.

Complexities aren't addressed in Peterson's book. Instead, he goes for the predictable points and gags. Instead of calling his book "Scam," Peterson should have called it, "Yo Momma!" That's about as complex as he gets.

CJL